July 23, 2024

The ties that bind

Assessing two decades of a European-African research partnership with an anxious eye on the future.

By Michael Dumiak

As thousands gather this week for the 25th International AIDS Conference in Munich, Germany, participants will be looking for the threads that tie together a quarter of a century of HIV/AIDS and the latest advances in treatment, prevention, and cure research.

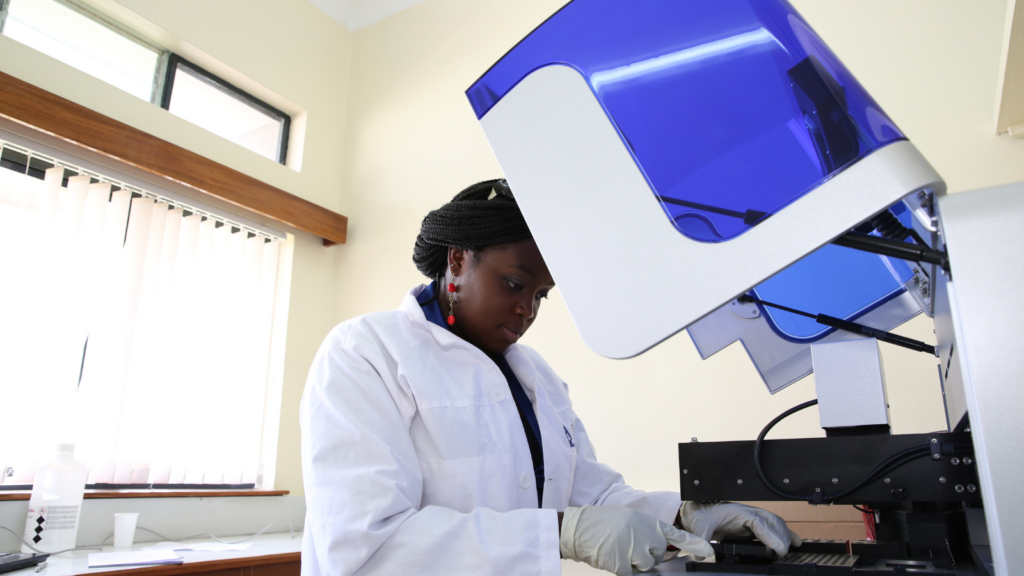

Something critical to the progress in battling this disease over the last 25 years is the tireless work that goes into building labs and clinics in the hardest-hit areas and cultivating the young infectious disease researchers, especially on the African continent, who tackle not just HIV but many neglected maladies such as Lassa fever and tuberculosis (TB).

One of the engines for this essential resource-building is the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership, or EDCTP. The partnership started under a kind of matching grant: €200 million from the European Commission and €200 million pledged from 16 European participating states. Its second iteration brought in 16 African countries to the partnership: states from the eastern, western, and southern parts of the continent.

Last November, 1,100 delegates attended a forum in Paris marking the partnership’s 20th anniversary. Over those two decades, the EDCTP has now grown to include 28 African country member states. During its first and second iterations the partnership put 401 researchers through junior or senior fellowships in Africa and has supported 1,618 research trainees, including 121 grants aimed at strengthening trial ethics and regulatory capacity. The partnership has underwritten 206 collaborative clinical research grants and fostered a total of 477 clinical studies, including 150 Phase 2 and 3 trials. The partnership also had a hand in pushing through the RTS,S and R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccines and a simplified treatment for cryptococcal meningitis.

More of EDCTP’s efforts will show up at the IAS conference this week when researchers share results from early-phase safety trials concerning monoclonal antibody therapies for children living with HIV, conducted by the South African Medical Research Council and European colleagues, and in a study underway in Zimbabwe on musculoskeletal health in children living with the virus. Meanwhile, in Lagos, Nigeria, a Phase 2 trial program of a Lassa fever vaccine candidate supported by EDCTP and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and sponsored by IAVI is underway. It is the first of the kind to be held in that country for 40 years. The first phase, conducted in urban settings with low Lassa transmission, is underwritten by CEPI. The follow-up will build on these results and be conducted in regions where Lassa transmission is higher. This later stage will get started in 2025 and be supported by CEPI and EDCTP.

The EDCTP took some time to find its feet, and it wasn’t always smooth. In its first three years, there were four different executive directors, two of them interim, as well as criticism aimed at slow distribution of funds and difficulty in keeping up with its pledged ambitions. But under the aegis of personalities like the late Pascoal Mocumbi, former prime minister of Mozambique and the first high representative for the African members of the partnership, and former Portuguese science minister and European parliament member Maria Da Graça Carvalho, the partnership held steady.

Now, as it enters its third decade, the EDCTP is getting a boost in funding from the European Commission, which makes up half of its budget. It plans to lay out priorities for newborn and child health among its participating states and advance women in health science. And as the enterprise is, after all, formed among partnerships, it is looking to shore up research connections and seed opportunities among European, African, and multilateral institutions, including what is hoped to be an increasingly influential Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or ACDC.

For Cape Town-based Thomas Nyirenda, EDCTP’s strategic partnerships and capacity development manager and head of its Africa office, this means better engagement with the emergent African Union. The African Union was launched in 2002 and until recently its relations with the European Union were often strongly aligned, Nyirenda argues, on geopolitical and food security issues. The ACDC is a more recent development.

“It had not been a very fruitful collaboration [with the African Union] going back to when we started in 2004, because we really didn’t have a framework,” Nyirenda says. “That’s changed.”

The EDCTP continues to create bridges among researchers and support clinical spaces in under-resourced communities that people have come to recognize and trust. As the Lassa fever trials shift into gear, trial participants are brought into clinics previously used in Abuja, Nigeria, by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in its Ebola program, at the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research in Accra, Ghana, and at the JFK Medical Center in Monrovia, Liberia.

But the plan, says Gaudensia Mutua, a medical director of IAVI clinical research at the University of Nairobi overseeing the trial, is to progress out of urban settings into more remote places and reaching into Sierra Leone. “We’re building on the infrastructure that was set up for Ebola,” Mutua says. The program will also welcome five new master’s students.

Mutua spent 16 years at the Kenya AIDS Vaccine Initiative (KAVI) research unit and recalls when new generators and lab equipment came onto the pediatric floor at the Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi where KAVI is based. Tomáš Hanke, a vaccine immunologist at the Jenner Institute in Oxford, remembers this, too. It was part of EDCTP’s support for new trials, including Hanke’s GREAT Partnership, which is advancing a chimpanzee adenovirus (ChAdOx1)-and-poxvirus MVA-vectored four-component conserved mosaic HIV T-cell vaccine candidate. Hanke also pursued two other research programs over the course of EDCTP’s tenure.

“It’s a way for sure to collaborate among labs,” says Carlos Martín, a microbiologist at the University of Zaragoza, meaning both with his peers in Europe and in African research centers. He and his colleagues designed an attenuated live M. tuberculosis vaccine candidate, MTBVAC, that is currently in trials. He worked with two EDCTP-backed programs 15 years ago, which is where he first worked with the TB trial clinics in South Africa that are being used now for MTBVAC. The network branches throughout northern institutions, providing an expansive platform for the European Commission to express its research agenda and seeding opportunities for researchers around the European continent.

EDCTP has also worked over the years to establish African clinical research platforms under what it calls regional networks of excellence, each branching into multiple countries and institutions. These regional networks are managed from Congo-Brazzaville, Uganda, Mozambique, and Senegal.

Thomas Nyirenda recently returned from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where he was doing one of the things he does best: build networks. He sees two big turning points in recent years for the EDCTP. One was the setup of ACDC in Addis Ababa in 2016. The other is the COVID-19 pandemic.

“An African-led, owned, and coordinated clinical trial ecosystem would be more sustainable.”

~ Thomas Nyirenda, EDCTP

The pandemic experience bolstered support for efforts to build and further develop local clinical trial programs based on the African continent, starting with early phase trials all the way through manufacturing products. “We call this the African clinical trial ecosystem,” he says. “In the past you would visit countries and ask, how do you support and fund research here? Show us your research agenda. They would give you a document with a list of diseases.”

This is not strategic, in his view. If the goal is to expand research and development of public health interventions, manufacturing capabilities, and to better use data tailored to local genetic variations and contexts in Africa, there needs to be more coordinated efforts and progress on fronts like setting standards for more common medical regulatory regimes, epidemiological surveillance, professional education, and confidence in secure data sharing.

ACDC is moving to put a continental health agenda in motion, and local and early-stage clinical trials should be part of it, says Salim Abdulla, principal scientist at the Ifakara Health Institute in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. “If we really want to expand manufacturing, local production, local delivery, having Phase 1 capabilities will be key.”

As EDCTP moves ahead, Abdulla wants to see more multi-center, multi-institutional collaborations emerge. But this will largely depend on funding, which in today’s climate is far from guaranteed. EDCTP’s budget through 2031 is €1.86 billion, yet there is anxiety and political instability both within Europe and among the African members of the partnership, and worries about how to fund efforts in the future. “We cannot guarantee external resources for Africa will be here forever,” Nyirenda says. “An African-led, owned, and coordinated clinical trial ecosystem would be more sustainable.”

But for now, the EDCTP will move ahead with its next decade of work, continuing to foster the advancement of young researchers and developing more capable labs, clinics, and manufacturing facilities across Africa. It will also serve as an indicator of the priorities of the European Commission for countering infectious diseases and preparing for future pandemics.

Michael Dumiak, based in Berlin, reports on global science, public health, and technology.

Read more:

- Africa CDC and the new public health order

- Profile of Ifakara Health Institute

- Impact with equity: EDCTP and equitable research partnerships, comment in The Lancet Global Health

- Evolution of a strategic, transformative Europe–Africa Global Health partnership—EDCTP3, comment in The Lancet Infectious Diseases