June 8, 2022

Is the next pandemic preventable?

COVID-19 has inspired many books about pandemic prevention, but reports show the world isn’t any better prepared today than it was before.

Kristen Kresge Abboud

“Outbreaks are inevitable. But pandemics are optional.”

This quote from Larry Brilliant, a renowned American epidemiologist and philanthropist who played a key role in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) efforts to eradicate smallpox, appears just two pages into the preface to “Stopping the Next Pandemic: How COVID-19 can help us save humanity,” by Debora Mackenzie.

Mackenzie acknowledges how incongruous this statement can seem today, given that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is estimated to have caused 15 million excess deaths worldwide. But she insists the principle is still true. “We can stop the next pandemic,” she writes. And if anything, the experience of the last two and a half years should shore up our willingness to do so. “Our job now is to take the political momentum created by COVID-19 and put global institutions in place to achieve that, and whatever else we need to save ourselves from the threat of pandemic disease.”

Brilliant’s quote also appears in “How to Prevent the Next Pandemic,” by Bill Gates, co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and an eminent philanthropist and business leader. That isn’t the only overlap between these two books, and others recently released on the topic, including “Preventing the Next Pandemic: Vaccine Diplomacy in a Time of Anti-science,” by Peter J. Hotez.

Each of these books describes some of the hard-won lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. There are the obvious ones, such as the importance of quickly developing vaccines and therapeutics, distributing personal protective equipment, communicating clearly and effectively with the public, and sharing information globally as soon as an outbreak occurs. Some of this went extraordinarily well during the COVID-19 pandemic — vaccines were developed faster than ever before — but much of it did not. “The world responded to COVID faster and more effectively than to any other disease in history,” writes Gates. However, he notes, there were also many failures. Chief among them is the failure to deliver vaccines to poor countries, and the world’s failure to prepare for and prevent pandemics from happening in the first place.

Scientists have been sounding the alarm about how unprepared the world was for future pandemics since 1992. In 2015 Gates delivered a TED talk on the topic, which has more than 36 million views on YouTube. Now, he and others are sounding the alarm even louder. And this time they are hoping the world will listen. “For all the effort that humans put into preparing for attacks from fires, storms, and other humans, we had not prepared seriously for an attack by the smallest possible enemy,” Gates writes. “It’s time we did.”

Gates and Mackenzie offer many similar suggestions on what the world can and should do now to be more prepared than it was when SARS-CoV-2 first appeared. The first is to prevent outbreaks from escalating to epidemics and pandemics.

To do this, they suggest creating a high-level, well-funded, collaborative pandemic prevention team. The idea is to have a group of specialists who are closely monitoring global health so that they can quickly spot suspicious clusters of new or existing infectious diseases and alert the world to their presence. Gates calls this team GERM for Global Epidemic Response and Mobilization and suggests it be managed by the WHO. He estimates the cost of running such a team to be around US$1 billion per year, which seems a small price tag when compared to the trillions of dollars COVID-19 slashed from the world’s economy and the millions of lives it took in the process.

The success of such a team will hinge on improving global surveillance systems and strengthening infrastructure to both detect and treat disease in many parts of the world, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. This is another point on which Mackenzie and Gates agree. “If doctors and epidemiologists don’t have the tools and training they need, or their national health agency is weak or nonexistent, we’re going to keep seeing outbreak after outbreak,” Gates writes.

Mackenzie and Hotez also focus on the importance of addressing the factors that give rise to infectious disease outbreaks in the first place. Spillover events, the term for when a pathogen that originates in animals is transmitted to and then among humans, are the likely cause of every viral pandemic that has occurred in the 20th century. And these events are expected to increase substantially in the future due to environmental destruction.

This is an area where Hotez’s expertise is on full display. His book summarizes how throughout modern history war and political unrest have been major drivers of infectious disease outbreaks, and how climate change and unregulated urbanization are increasingly promoting the emergence and spread of infectious and tropical diseases. He also describes how all these determinants of infectious disease outbreaks are inextricably linked to poverty, what he calls “the king of all determinants.”

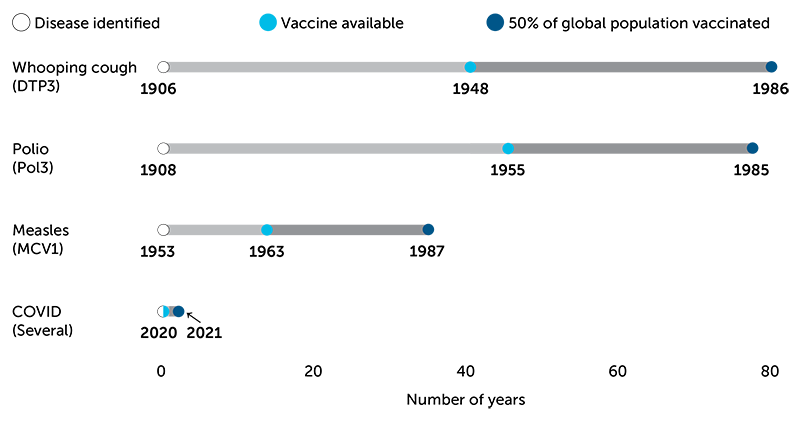

All three books also delve into how to improve the response to epidemics or pandemics that do occur despite the world’s best efforts to prevent them. The first COVID-19 vaccines were authorized within a year of when the viral sequence of the novel coronavirus was first published. Fast, but not fast enough. To better control future pandemics, vaccines and therapeutics will need to be developed even more rapidly. This will likely involve using some of the highly adaptable platforms that were proven in the COVID-19 pandemic, such as mRNA, but will also likely involve applying advances in other areas, including machine learning and artificial intelligence. “We need a lot more basic work on diagnostic, vaccine, and drug technologies, and we need to deploy the capabilities we have so we are ready to use them, fast, and everywhere,” writes Mackenzie.

Although COVID-19 vaccines were developed and delivered faster than ever before, experts suggest timelines will need to be compressed even more to prevent future pandemics. Source: “How to Prevent the Next Pandemic,” by Bill Gates/Our World in Data.

Although COVID-19 vaccines were developed and delivered faster than ever before, experts suggest timelines will need to be compressed even more to prevent future pandemics. Source: “How to Prevent the Next Pandemic,” by Bill Gates/Our World in Data.

Equitable and timely access to vaccines and therapeutics, what Mackenzie means when she says “everywhere,” is another critical component of pandemic response. This may be one of the most glaring lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, and entire books are probably being written on this topic.

Gates suggests the world’s vaccine plan should include “a way to allocate doses so they provide the greatest benefit for public health and don’t simply go to the highest bidders.” This was what ended up happening with COVID-19 despite COVAX — the global initiative led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Initiatives (CEPI), Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, and the WHO, which was established to ensure COVID-19 vaccines are available worldwide — and is partly why even now vaccination rates lag far behind in low-income countries.

Hotez devotes a large portion of his book to access, which he refers to as vaccine diplomacy. He defines it as: “a subset or specific aspect of global health diplomacy in which large-scale vaccine delivery is employed as a humanitarian intervention.”

Health diplomacy, though not vaccine related, was done to tremendous success with the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) as described recently in this article by veteran AIDS activist and writer Emily Bass. PEPFAR transformed HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention efforts in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, and although COVID-19 is a different pandemic than AIDS, the same lessons apply: “Ensuring global equitable access to vaccines, tests, and effective antivirals, with a focus on reaching the highest-risk people, will save lives,” Bass writes.

PEPFAR proved this was possible. Now, a similar approach is needed not just for COVID-19, but future pandemics too.

Coordinating this, and the other pandemic prevention and response efforts, will require a concerted global effort. And there is no better time to start that effort than now, while the devastating consequences of COVID are still fresh in everyone’s minds. Yet a panel set up by the WHO warns that the world is no more prepared to face future pandemic threats than it was when SARS-CoV-2 emerged. The co-chairs of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response had this to say in the foreword to the report: “Now is the time to transform the international system for preparedness and response — and not merely tinker with it. At the present pace of change, the world is laying the groundwork for failure and the risk of a new pandemic with the same devastating consequences.”

Bold action is required, and these books offer a clear description of what those actions could and should be.