February 27, 2023

HIV with a touch of gray

More and more people living with HIV are over 50 years old, raising new questions about efforts to slow the aging process in a population of individuals on antiretroviral therapy.

Michael Dumiak

There was once a time when it did not seem that a large and aging cohort of people living with HIV would be a top concern, simply because it did not seem likely there would be such a thing. But now there are large numbers of people aged 50-plus living with HIV — and therefore having taken antiretroviral therapy, in some cases for decades — around the world, not just in wealthier countries.

This image was created using OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 AI system.

This image was created using OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 AI system.

This is good news. It’s something to marvel at, both for scientific ingenuity and for sheer human perseverance. But for some time, it’s also concerned researchers that long-term use of antiretrovirals, and living with the virus itself, would be a cause of adverse health effects — an enlarged heart and liver and an increased risk of noncommunicable diseases, osteoporosis, kidney disease, or other unknown factors. This is particularly concerning when added to the list of conditions that also commonly appear or intensify with age, which is why the subject of aging with HIV is drawing increasing attention.

In higher income countries, a third of adults living with HIV are 50-plus, and in the U.S., that figure is closer to 50%. Katy Godfrey, an infectious disease physician and senior technical advisor for adult care and treatment at the Office of the Global HIV/AIDS Coordinator, an arm of the U.S. State Department, recently told an online panel that the number of people over 50 on antiretroviral therapy has also grown substantially in the last five years in the groups supported by PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

PEPFAR supports 20 million children, men, and women on antiretroviral therapy in more than 50 countries: South Africa, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Tanzania are among the largest. By far the majority are over the age of 40 and a substantial number are over 50 years old, according to PEPFAR figures. “The largest group of people supported by PEPFAR are women over the age of 40,” she said. “With any luck, they will age into the next cohort. We’re trying to make that happen as well as we can.”

It appears well within reach, but there are going to be some challenges. Compared to people aging without HIV, some analyses suggest people growing older while living with the virus experience a greater burden of the complications that come with aging, including cognitive difficulties, kidney, liver, and cardiovascular disease, and frailty.

Godfrey’s panel appearance was follow-up to research published in a special issue of the Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS) on growing older with HIV in what it calls the ‘treat-all era,’ a time when access to antiretroviral therapy is both accessible and mandated when infection is discovered. The journal Viruses is also planning a special issue on aging with HIV with a focus on studies employing sex or gender-based stratified analyses, as well as research on aging among women or gender minorities with HIV. Emory’s Center for AIDS Research has hosted at least two conferences on HIV and aging, with plans for more.

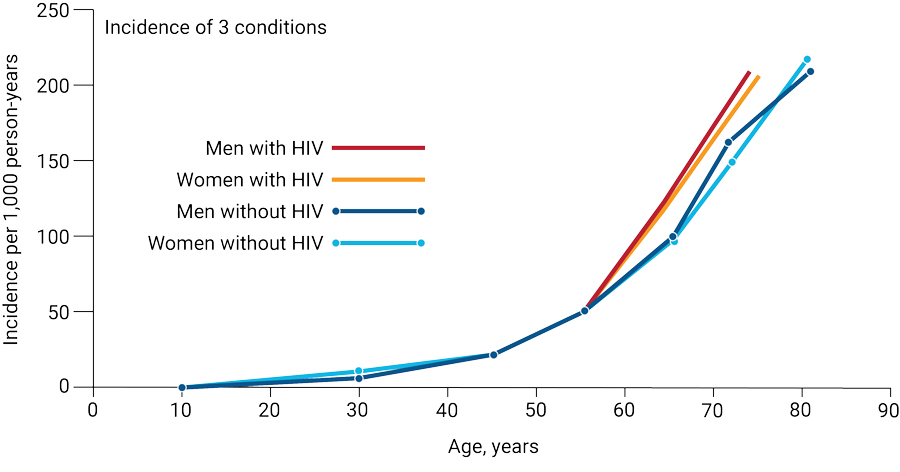

Reframing aging in the context of HIV. HIV adds another layer of complexity in developing approaches that can delay or prevent the onset of multiple chronic conditions that coincide with normal aging. Source: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 89(S1):S34-S46, February 1, 2022.

Reframing aging in the context of HIV. HIV adds another layer of complexity in developing approaches that can delay or prevent the onset of multiple chronic conditions that coincide with normal aging. Source: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 89(S1):S34-S46, February 1, 2022.

George Kuchel, director of the University of Connecticut’s Center on Aging, says an increased focus on older people living with HIV comes not just because the population is growing, but also because gerontologists and researchers in the emerging field of geroscience think there may be future therapeutics and pharmaceutical interventions that could make a difference in managing chronic illness that comes with age. The idea is to extend not just a person’s lifespan but to promote a better and healthier quality of life during those years.

Kuchel delivered a plenary on this topic at the recent Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2023) in Seattle. He is collaborating with researchers in Chicago and Minnesota, including Mary C. Masters at Northwestern University, to push research for interventions aimed at alleviating chronic illnesses and multi-morbidities specifically with older people living with HIV in mind.

“Aging is inevitable. But how we age, and how quickly we age, is not,” Kuchel says.

He says the forces at work in someone living with HIV and developing aging issues in their 50s are not the same as someone who is 80 years old, without HIV, and developing similar conditions. “We need to learn from both what’s common, and what’s similar, but also carefully think about what’s different,” he adds.

Jules Levin, an AIDS activist and director of the National AIDS Treatment Advocacy Project, says one big difference that he sees is the earlier onset of the symptoms of aging. “People with HIV suffer premature or accelerated aging, more comorbidities than people without HIV if they are over 50 or 60, at similar ages,” he told the JIAS panel, citing among other things research findings presented in 2020 by Julia Marcus stemming from a Kaiser Permanente cohort analysis of insured adults, the cohort including 39,000 people living with HIV.

The scientific explanations for this are still being investigated. One area of research involves the so-called age clock, or epigenetic DNA methylation, in which a molecular process adds methyl groups to particular regions of DNA strands in the human genome. Researchers think methylation could be a marker for healthy or unhealthy aging. Some studies have found that HIV affects methylation, suggesting it can even speed up the process, thereby implicating the virus in earlier onset of aging.

But looking ahead — as societies age overall and aging research accelerates — it may become harder to parse what is directly connected to HIV, and what is a more widely felt element of growing older. And it may very well vary geographically.

Zahra Reynolds, a research manager at the Medical Practice Evaluation Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, found after interviewing a group of people in Uganda living with HIV with a median age of 57 that, overall, respondents living with HIV in this small group considered themselves as healthy or healthier than people living without the virus. While people in the group with HIV rarely considered their HIV status a barrier to a healthy life, nearly all respondents — irrespective of HIV status — were concerned about memory loss, physical pain, and loss of energy, and how these health issues would affect their daily living and livelihood.

Prolonging the onset of these common symptoms of aging, as well as those related to other health issues that crop up as we grow older, has the potential to be a world-changing boon, both for those living with HIV and other chronic conditions, and those who aren’t.

Michael Dumiak, based in Berlin, reports on global science, public health, and technology.

Read more:

- The Well Project, HIV research focused on women and girls

- Aging with Pride

- Sanyu Mojola, sociologist, on HIV after 40 in rural South Africa

- The Graying of the AIDS Epidemic: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 2003