December 3, 2024

Outthinking and outsmarting HIV to outdo an epidemic

Can we outsmart a virus so clever and evasive that it has challenged scientists for decades? My research seeks answers to these pressing questions.

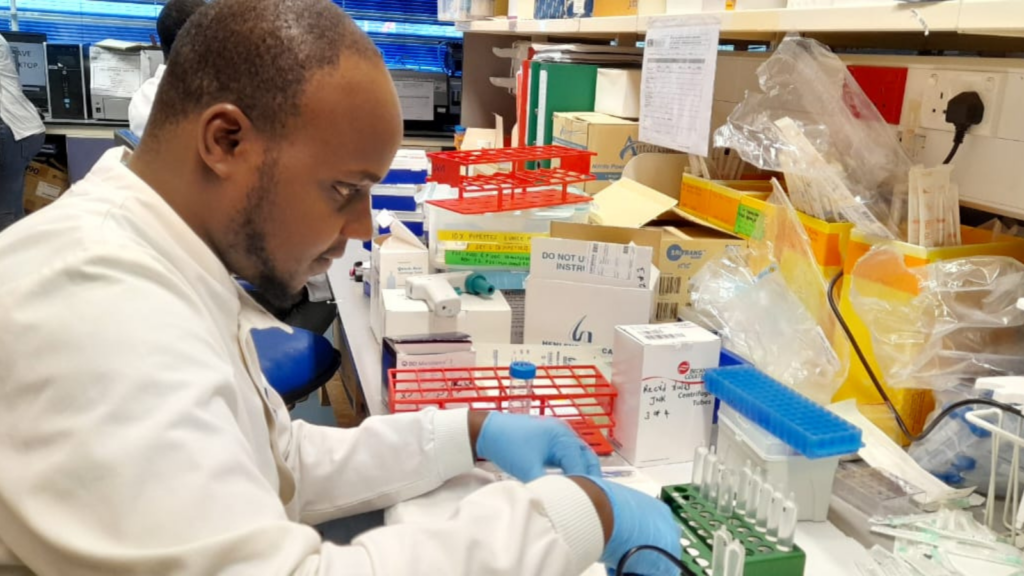

By John Kimotho

For over four decades, the world has fought tirelessly to close the tap on new HIV infections. Yet, this relentless virus continues to plague sub-Saharan Africa, draining health resources from systems stretched thin by the burden of malaria and tuberculosis. Africa had hoped to end these diseases by 2030 under the AU Catalytic Framework, but the road ahead remains fraught with challenges. Adding to this strain are emerging infectious diseases and the escalating impact of climate change, which no longer resides in theory but manifests in real-life health consequences, further stretching already overburdened health systems.

In my lifetime, I have witnessed the remarkable progress made in HIV prevention — through pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), treatment-as-prevention strategies, and awareness campaigns. Yet, gaps in adherence and uptake reveal a deeper truth: we need a long-term solution to close the tap on new infections — an HIV vaccine.

This quest for a vaccine against HIV fuels my passion as a young African scientist. For nearly 30 years, the scientific community has rigorously pursued this goal. But could we work smarter, faster, or more effectively to achieve this elusive breakthrough? Can we outsmart a virus so clever and evasive that it has challenged scientists for decades? My research seeks answers to these pressing questions.

Outthinking HIV through the germline targeting approach

HIV’s complexity has forced scientists to think outside the box to outsmart the virus at every turn. One promising innovation is germline targeting, a cutting-edge vaccine design strategy. This approach “trains” the immune system to produce specialized antibodies — akin to elite soldiers — capable of fighting even the most evasive viruses like HIV. The process begins by stimulating “starter cells” (naive B cells) with carefully engineered immunogens, gradually shaping them into strong defenders, also known as broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs).

Think of it this way: If developing immunity is like growing a tree, germline targeting involves selecting the best seed (a specific B cell) and nurturing it with the right soil, water, and sunlight (vaccine components). The result? A strong, resilient tree (an immune response) that thrives even in harsh conditions.

This approach is being explored by numerous scientists and one of these immunogens is the eOD-GT8 60mer pioneered by Dr. William Schief at Scripps Research and advanced by scientific partners like IAVI. This immunogen has already shown promise in studies such as the IAVI G001 and has further advanced to clinical trials in Africa through IAVI G003. As an IAVI Early Career Investigator, I am proud to contribute to this exciting frontier.

“If we can outthink the HIV virus in the lab, we can outdo the AIDS epidemic outside the lab.”

~ John Kimotho

Why the African context matters in this quest

While germline targeting offers exciting possibilities, its success depends on understanding the nuances of the populations it’s intended to serve. Besides the genetic background which will be important for priming these responses, environmental factors such as infections will be an additional challenge. This is where my research comes in.

As an IAVI Early Career Investigator based at KEMRI-Wellcome Trust in Kilifi, Kenya, my work focuses on how environmental factors, like chronic infections, shape the immune system — particularly the B-cell compartment. For instance, chronic malaria exposure — a reality for many in Africa — can impair immune function, altering the effectiveness of vaccines.

Using malaria as a proxy for chronic pathogen exposure, my research analyzes how these environmental pressures influence baseline immune profiles and responses to germline-targeting HIV vaccines. Preliminary findings suggest that cumulative malaria exposure restructures immunological profiles by causing heightened memory B-cell activation and exhaustion and maintains an activated state of systemic inflammation which allows high-exposure individuals to handle frequent antigenic stimulation without succumbing to chronic inflammation. This immune tolerance mechanism of immune cell exhaustion and systemic inflammation may potentially lead to less responsiveness to vaccines and novel pathogens and may also lead to poor maintenance of vaccine-induced responses.

These insights could help tailor immunogen designs and dosing strategies to ensure vaccines are effective for populations in Africa. What works in high-income countries often needs to be adapted for regions burdened by unique environmental and health challenges.

Enabling African scientists to pioneer groundbreaking efforts towards ending HIV

Programs like the IAVI Early Career Investigator Award have been instrumental in enabling young scientists like me to pursue research that directly impacts our communities. Through the ADVANCE Investigator-Initiated Research (IIR) program, supported by USAID through PEPFAR, early-career scientists have the chance to channel curiosity into impactful research, producing findings that could alter the course of global health for the better.

But I am not alone. The IIR program supports many African researchers, including women scientists, who are advancing critical work in immunology and vaccinology. These programs do more than fund research — they advance a sense of ownership and leadership among African scientists, empowering them to address the unique health challenges of the continent. The IIR program’s funding for research, known as IIR Awards, is offered through a competitive call for proposals open to all IAVI clinical research center partners. The awards range from US$10,000 to $100,000. Additionally, to encourage mentorship of early-career investigators by seasoned researchers, the IIR program offers grants of between US$200,000 and $250,000 for innovative and collaborative research.

As an African scientist, I am honored to stand shoulder to shoulder with global peers, pushing the boundaries of science to deliver solutions that our continent needs most. On this World AIDS Day, a day of reflection and action, I remain hopeful that we can fast-track this progress through innovative approaches like germline targeting to pave the way for an effective HIV vaccine. A vaccine that could bring us closer to ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

To achieve this, we must continue investing in science and empowering young scientists to take the work on. If we can outthink the HIV virus in the lab, we can outdo the AIDS epidemic outside the lab — in the world.

About the author: John Kimotho, is a second-year SANTHE Ph.D. fellow and an IAVI Early Career Investigator Awardee, based at the KEMRI Wellcome-Trust Research Program in Kilifi, Kenya. John holds a Master’s degree in Immunology from Pwani University and a Bachelor’s degree in Medical Laboratory Science from the University of Nairobi.