November 12, 2024

Careers dedicated to science in service of humanity

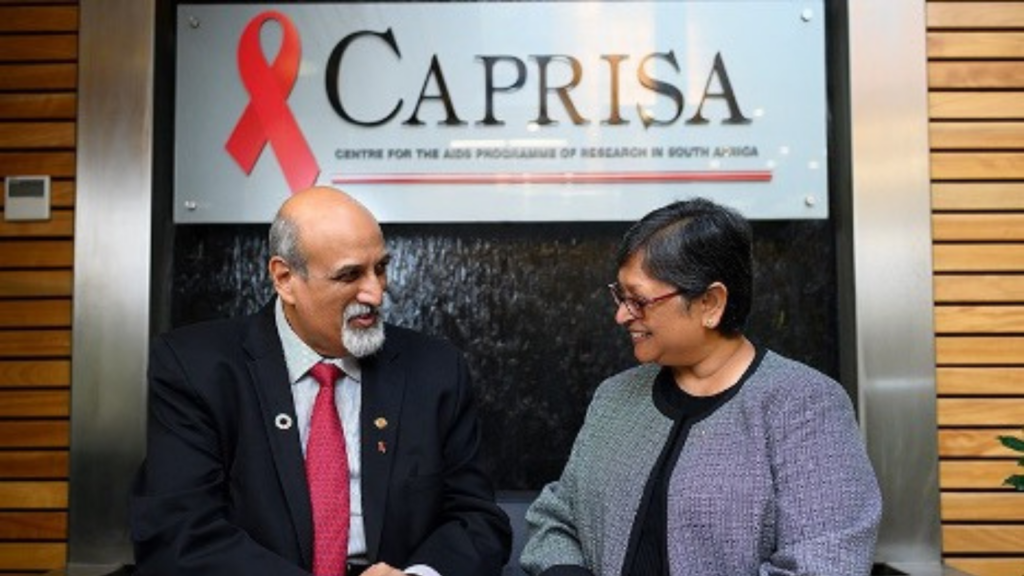

Quarraisha and Salim Abdool Karim received the Lasker Prize for public service in recognition of their decades-spanning work on HIV prevention, treatment, and advocacy.

By Kristen Kresge Abboud

In 2011 we featured an interview with the husband-and-wife duo Quarraisha and Salim Abdool Karim in an article titled Chemistry Lab. The story, which is definitely one of my favorites in the IAVI Report archives, featured the lives and work of four prominent HIV research couples who “successfully intermingle science and love.”

The vignette on the Abdool Karims details their scientific meet cute, which happened in a university laboratory just five days before Salim was leaving South Africa to study epidemiology at Columbia University. After a short but very long-distance courtship, the two were married. Quarraisha then joined Salim in New York City, where she also studied epidemiology at Columbia.

Ever since, they have divided their time and careers between the two continents. Both serve as professors at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and as heads of CAPRISA, the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, where most of their research takes place, in addition to various other appointments. They’ve now been married 40 years; 35 of them spent researching HIV/AIDS together.

That is inspiring in and of itself. But now there is even more reason to draw inspiration from the Abdool Karims. This power couple was recently awarded the 2024 Lasker-Bloomberg Public Service Award at an elaborate ceremony in New York City for their work on “illuminating key drivers of heterosexual HIV transmission; introducing life-saving approaches to prevent and treat HIV; and statesmanship in public health policy and advocacy,” according to the Lasker Foundation’s announcement.

The prize, often referred to as “America’s Nobel” or even the Oscars of science, which comes with a US$250,000 honorarium, was a great honor for the duo, and its prestigious awards ceremony capped a long list of accolades and recognition they have received for their decades of service in combatting HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases, including tuberculosis (TB) and COVID-19. “This recognition is humbling but is also a powerful reminder of the transformative role of science in shaping an inclusive and just world,” says Quarraisha.

We spoke recently on a video call, the professors back in their office in South Africa in front of a wall of photos and awards they and their team of researchers at CAPRISA have amassed over the years. But winning the Lasker was the pinnacle. What made this award particularly special to them was being recognized not just for their scientific contributions, but for how these contributions helped society at large. “This award recognizes the value of advancing public health,” says Salim. “And the fact that it was awarded to African scientists, whose work primarily takes place in Africa, sends an important message to all African scientists,” he adds. “We are recognizing the power of global solidarity to have global impact. This is deeply imbued in our work in HIV research and prevention over the past 35 years.”

This work started in earnest when Quarraisha and Salim completed their studies at Columbia and returned to South Africa in 1988. As they left the U.S., the horrors of the HIV pandemic were just becoming visible. When they returned home to South Africa, the country was still living under apartheid and so they took on roles as scientists and activists, battling apartheid and at the same time seeking to understand where in their communities HIV might be lurking.

At that time, few researchers in the country were concerned with this new virus. The Abdool Karims set out to change that. They started by conducting community surveys to determine the prevalence of HIV infection. What they found shaped their research for decades to come. “We found that, in Africa, young women bore the brunt of HIV, unlike in the U.S., where men who have sex with men were primarily becoming infected,” Quarraisha says.

Their studies pointed to a dramatically higher prevalence of HIV in girls and young women, exemplifying the power dynamics of sexual interactions that were at play and that would fuel the epidemic in the country, eventually making South Africa home to the largest number people living with HIV anywhere in the world.

In 2002, five institutions (the University of KwaZulu-Natal, University of Cape Town, University of Western Cape, the South African National Institute of Communicable Diseases, and Columbia University) helped established CAPRISA, a non-profit AIDS research organization with the Abdool Karims as its leaders. Its focus was to reduce HIV/TB co-infection deaths and prevent new HIV infection among young women and girls. “We focused on developing and testing technologies that empowered women,” Quarraisha says.

It took 18 years for these efforts to pay off. In 2010, at the International AIDS Conference in Vienna, the Abdool Karims announced the results of a trial they led which found that a vaginal gel containing the antiretroviral tenofovir reduced HIV incidence in women by 39%.

This may not sound as remarkable today as it did then. In 2010 there weren’t any female-controlled HIV prevention options and so this was deemed a tremendous success, one worthy of a standing ovation for the Abdool Karims in the Vienna conference hall. “The efficacy wasn’t even that high,” Salim recalls. “But back then it was a huge advance.”

“In a world wracked by division, conflict, and war, this award is a sober reminder of how science reminds us of our shared humanity across the world.”

~ Salim Abdool Karim in his Lasker acceptance speech

Since then, there has been incredible progress in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), including highly effective oral and long-acting injectable formulations and greater access. “Today PrEP is used in over 100 countries around the world,” Salim noted in his Lasker acceptance speech. And the efficacy of the approaches has improved dramatically since that 39% finding. At the 2024 International AIDS Conference this past July, researchers presented data from the PURPOSE trial showing that a twice-yearly injection of the antiretroviral lenacapavir was 100% effective at protecting cisgendered women in Uganda and South Africa, including a CAPRISA cohort, from acquiring HIV.

The promise of lenacapavir has led some researchers to question the potential role of other HIV prevention options in the pipeline, including HIV-specific broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. One of these antibodies, CAP256V2LS, is an engineered version of a broadly neutralizing antibody (bnAb) first identified in one of CAPRISA’s cohorts and it is in the early stages of clinical development by CAPRISA researchers either alone or in combination with another HIV-specific monoclonal antibody. But given the high efficacy of lenacapavir, Salim, a principal investigator of the trials involving the antibody, thinks bnAbs may only play a much more circumscribed role. “Personally, I don’t see a future for the bnAbs in prevention,” he says, noting the high cost of making and delivering antibody infusions as well as the high bar of protective efficacy established by the lenacapavir injections which makes even designing studies of bnAb-based prevention rather challenging. He does, however, see a potential role for bnAbs in efforts to cure HIV infection.

Still, Quarraisha and Salim both know that the biggest challenge with lenacapavir or any new modality is showing its effectiveness not its efficacy. “It’s not what we have in hand that matters but what we can get to people,” says Quarraisha. And whether it is access to new longer-acting PrEP options such as lenacapavir, COVID-19 vaccines, or other yet-to-be-invented interventions, HIV has set the standard for equitable access, according to Salim, through a combination of activism and mobilization, novel licensing and tiered-pricing agreements with pharmaceutical companies, and global solidarity.

Global solidarity is something they have impressed upon the numerous scientists they have both mentored throughout Africa. “We can’t think of problems in the global south as just problems for the global south,” says Quarraisha. Their advice for the next generation of scientists is to persevere and to let go of any expectation of instant gratitude. “Great contributions take time,” says Salim. “You have to make all the mistakes first and then keep trying new things.”

Read more: CAPRISA Celebrates 20 Years of Public Health Progress