June 29, 2021

Leading Africa’s COVID-19 response

John Nkengasong warns against complacency setting in as vaccines trickle into many African countries.

Kristen Jill Kresge

John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), is one of the World’s 50 Greatest Leaders, according to Fortune magazine.

Coming in fourth among the top leaders recognized on the U.S. magazine’s annual list, Nkengasong was lauded for his pivotal role in steering Africa’s response to COVID-19, including instituting curfews and mask mandates early on. These simple public health measures have, at least in part, helped many places on the continent avoid the catastrophic mortality rates that have occurred in North and South America, Europe, and Asia.

Last year Nkengasong was also awarded a Global Goalkeeper Award by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The Foundation described Nkengasong as a “relentless proponent of global collaboration and evidence-based public health practices, and a champion for minimizing the social and economic consequences of COVID-19 across the African continent.” He also serves as a Special Envoy on COVID-19 Preparedness and Response to the World Health Organization’s Director General, Tedros Ghebreyesus, and is a member of the board of directors of IAVI and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Initiatives (CEPI).

A native of Cameroon, Nkengasong is a virologist by training with more than three decades of experience in public health. Prior to heading the Ethiopia-based Africa CDC, a specialized unit of the African Union, he was the acting deputy principal director of the Center for Global Health at the U.S. CDC and associate director of laboratory science and chief of the International Laboratory Branch at the Division of Global HIV/AIDS and TB.

In 2019, the Global Health Security Index ranked 195 countries based on their health security capabilities. The U.S. ranked first. The majority of African countries ranked among the “least prepared.” As COVID-19 began its deadly march across the globe, many warned of the potential for dire outcomes in Africa, where some public health systems were seen as wholly unprepared to be battling yet another infectious disease. But mortality rates remained surprisingly low on the continent, while deaths in the U.S. and other wealthy countries soared.

There may be various explanations for this difference, including limited testing capacity in many African countries, poor case reporting on the continent, and the fact that the African population is overall younger and therefore at lower risk of the deadly complications of COVID-19. But these factors may not tell the whole story, as Agnes Bingawaho, vice chancellor of the University of Global Health Equity in Kigali, Rwanda, and colleagues note. Writing in the Annals of Global Health, she says that many African countries have successfully contained their COVID outbreaks by implementing simple evidence-based interventions: social distancing, hand washing, mask wearing, contact tracing, and lockdowns.

Nkengasong acknowledges the role the continent’s early response to SARS-CoV-2 played in limiting its spread, though he warns against a wave of complacency he sees setting in in many countries. And with vaccine distribution lagging far behind even what the global community had anticipated, he is now more convinced than ever before that Africa needs to ramp up its capacity to manufacture vaccines for use within its borders. In April, the Africa CDC and the African Union held a two-day vaccine summit at which leaders pledged to boost vaccine production capabilities on the continent from its current level of supplying 1% of the African vaccine supply to 60% by 2040.

I spoke with Nkengasong in April about Africa’s response to COVID-19 and his vision for the role of the Africa CDC in facing future infectious disease outbreaks on the continent. An edited version of our conversation appears below.

How would you describe the current situation with COVID-19 in Africa?

The COVID situation in Africa is, in my view, still evolving, and no one should be complacent at all about that. We are not out of the woods yet. This is a tricky virus that can surprise you at any time, and because there is political fatigue setting in, we have to be careful. What is going on in India today is a wakeup call for Africa.

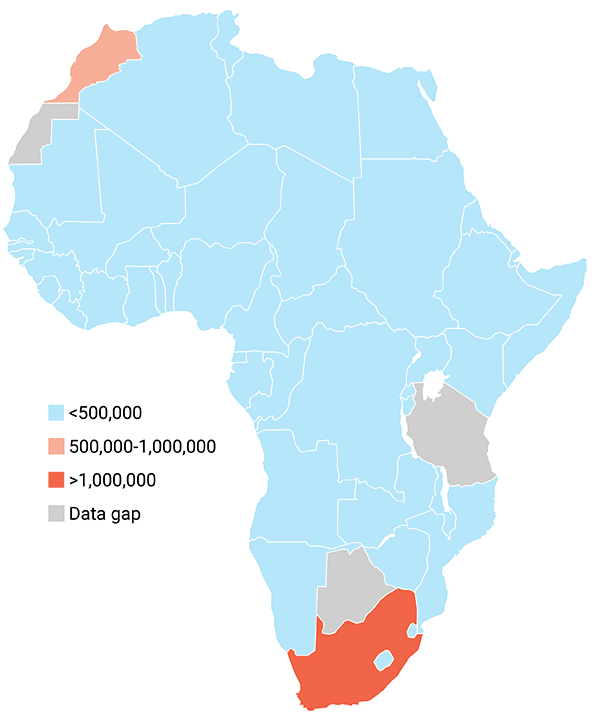

Total confirmed cases of Coronavirus in Africa (as of June 28, 2021). Source: Johns Hopkins University

Total confirmed cases of Coronavirus in Africa (as of June 28, 2021). Source: Johns Hopkins University

But, so far, the continent has avoided the high mortality rates from the virus seen in other parts of the world. What do you attribute that to?

We should make a distinction between the extent of the spread of the virus and mortality. Clearly, in Africa the virus has spread far beyond what we currently know. As we speak today*, the continent has reported about 4.6 million cases of COVID-19, but that is an underestimate because the serologic data show much more virus than that. If you just look at the serologic data coming out of Lagos, Nigeria, it shows a prevalence of about 20% and that’s a city of 20 million or so people. That means there are probably two million people in that city alone that are infected with this virus.

But there are factors that have limited overall mortality, including early political leadership and early responses aimed at controlling virus spread. Doing the right things early enough has kept us where we are. And while 126,000 deaths, which is what have been so far reported for the continent, may not be a full account of mortality, I don’t think the real number of deaths is five times that or even double that. If the deaths are there, you see it. You cannot hide that. In India we saw all these people being rushed into hospitals, but that isn’t happening in Africa now. What we know is that there are many people who are infected here, but not so many people who are falling sick. Still, we have to continue to be careful because with the variants that are emerging, we can very quickly be surprised.

How is the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines progressing in Africa?

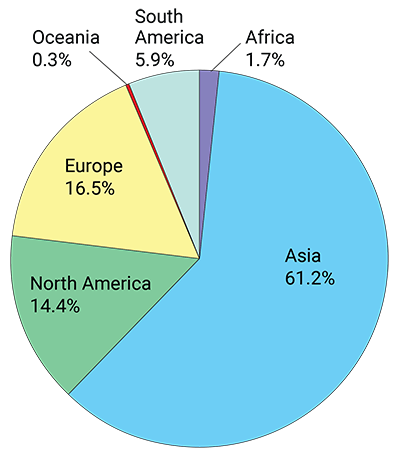

Unfortunately, the rollout has not gone the way we anticipated. Even if you look at COVAX’s own projections, we are way, way off from their goals. Our projection is that we need to immunize about 750 million people overall. By the end of this year, we were hoping we would have vaccinated at least 30% of them so that next year when the vaccines become more readily available and the distribution systems are in place, we can actually achieve our target of immunizing at least 60% of our population. But as a continent, we are really falling behind our targets, and it’s very concerning. That is not anything we can be proud of, and it speaks to the fact that if we are not very careful, this virus may surprise us by becoming endemic, and that’s not what anyone wants.

How has the dire situation in India and the fact that the Serum Institute isn’t exporting vaccine doses affected Africa’s vaccine supply?

The situation in India has made vaccination efforts in Africa extremely complicated. Limited supply has been one of the biggest factors overall in terms of vaccine rollout on the continent.

Will COVID be the impetus for Africa to develop its own low-cost vaccine manufacturing capabilities?

Absolutely. That is why in April we hosted a vaccine conference with the African Union that involved about 40,000 people across the world to discuss vaccine manufacturing in Africa. I don’t know of any event, even the United Nations General Assembly, that has attracted more people, so this really stood out as one of the best opportunities in the pandemic. The goal was to make sure that we have a coordinated effort to advance the discussion of manufacturing vaccines on the continent and we are now working to build the right partnerships to promote that idea. As with any new idea, you have to promote it and manage the discussions very well and I continue to hope that there will be full alignment on this issue.

Do you think there are lessons on vaccine access and distribution from COVID-19 that are applicable to other diseases, including HIV?

Well, there are some similarities with COVID, but also a lot of differences. One fundamental difference is that HIV doesn’t affect the world in the same way that COVID does. There are 7.8 billion people in the world that are in need of a COVID vaccine now and that is not true for HIV. When HIV vaccines become available, access will be restricted to certain areas that are most in need, and that is many parts of Africa, so we will not see the same issues with access to an HIV vaccine that we are seeing with COVID vaccines today. The access issue for a potential HIV vaccine will be cost, not availability.

COVID-19 vaccine doses administered by continent* (as of June 27, 2021).

COVID-19 vaccine doses administered by continent* (as of June 27, 2021).

* Total number of vaccine doses administered. This may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, as most vaccines require two doses. Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data

Do you have an understanding of how willingness to be vaccinated against COVID varies across Africa?

Yes. We did a survey last year in which we asked a fundamental question: if COVID vaccines were here, would you take them? The survey included about 15,000 people from 15 African countries. The outcome was that acceptance ranged from about 60% in the Democratic Republic of Congo to about 95% in Ethiopia. But we don’t know how that has changed since there have been some concerns raised about some vaccines, including the one from AstraZeneca, which was halted for a time by the Europeans, and the vaccine from Johnson & Johnson, which was stopped temporarily in the U.S. I can’t speak to how that has affected people’s confidence in the COVID vaccines, but I know that it was originally very good.

What would you like to see from the second-generation COVID vaccines that would make them more feasible for global use?

I think for us the best vaccine is the vaccine that is available. I’ve said several times that you have to go with what you have, not what you need. And if that’s the AstraZeneca vaccine, let’s use that. But in my view, once the Johnson & Johnson vaccine becomes available it will be the best programmatically because there’s nothing as good as jabbing somebody once and not having them have to come back. You can also store it easily, so it has a lot of advantages in terms of vaccine rollout. But there is not one vaccine that will get us there. We will need to use a combination of vaccines to fight this war.

How has COVID changed your thinking about what the Africa CDC can do to prepare for future pandemics?

I think that the Africa CDC, as a young, specialized institution, needs to step back and be courageous. The current global architecture, which is very top down, was set up when the continent of Africa had 250 million people. Today, we are 1.3 billion people. I use this crude analogy to describe the situation: The house that your great grandparents built may years ago is probably a very different house than what you need today. You need to remodel it somehow so you can accommodate today’s family. That’s what we need to do. The architecture we settled on in 1947 after the Second World War is no longer working for us in developing countries. We need to have a global mechanism for health security, but we also need regional and national health security. We need to start by more effectively coordinating regional efforts and enhancing collaboration and communication within the regions. Then we’d also like to strengthen and empower the African CDC. You see what the Europeans are doing now with the European CDC — they are saying they need to be more empowered. The continent of Africa should be doing the same thing. It just takes political will and courage to make those things happen.

* Interview took place in April 2021. For current statistics click here.